Acupuncture Treatment of Depression, Distraction, Addiction and Mental Fixation: Recognizing the Ghosts in Our Heads

“Half the people in the world are deluded by ghosts, and half are confused by other people. Getting each other all excited, they practically fill the world. Those of lofty illumination try to save them by speaking clearly, but they do not heed. Those in positions of authority try to restrain them by law, but they do not stop. False doctrines increase in popularity day by day – in the future, who knows where it will end?” Cultivation of Realization by Unknown.

Classical Chinese Medicine frequently speaks of “ghosts” in its literature. This is often a bit alienating to our non-superstitious modern mind. Some say the ancient Chinese were talking about the spirit world, others think “ghost” is a metaphor for addictions, delusions and obsessions. Regardless of our stance on superstition in regards to ancient medical traditions, the study of “ghosts” is important within the understanding of Classical Chinese Medicine.

The word “ghost” is translated as “gui.” It is seen as a type of “phlegmatic” condition that affects the mind and emotions. Whether the “gui” is an actual “ghost invasion,” as some like to say, or a fixation that has manifested into an accumulation of blood and fluids, is inconsequential. In both cases “gui” distract the mind, scatter the spirit and weaken the will. It may even lead to destructive or compulsive behavior.

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) Taoist book Cultivation of Realization says “Ghosts are people who have already died; people are ghosts who have not yet died.” The image of a “ghost” is a wandering spirit, often fixated on a particular desire in the future or memory in the past. They can be distracted, sad or malevolent. In literature, ghosts often appear distracted: living outside of the present moment, unable to move on. They tend to attach to living beings, usually those of us who share a type of resonance with them: similar fixations.

Chinese medicine views disease as resulting from internal causes as well as external. Climatic factors such as “wind, cold, heat and damp” can attack the body to create illness. “Gui” is seen as a type of external factor, similar to that of pestilence or parasites. Like a bacteria, tick bite or virus the gui attaches to the body, moves inward and disrupts normal physiology.

In our modern understanding of mental health, “gui” conditions could be classified as mental-emotional states that distract us from the central thrust of our lives. Some would describe it as feeling like a cloud is in their head, or even “hanging over” their head, causing them to feel heavy and unclear. Others would describe it as feeling like some type of “bad energy” or negativity is around them, that they might have picked up somewhere. This can manifest states of depression, procrastination, distraction, “acting out,” obsessive-compulsion and various other personality disorders. The “phlegm” or turbidity that accumulates in our heads and limbs inhibits us from thinking clearly and acting decisively.

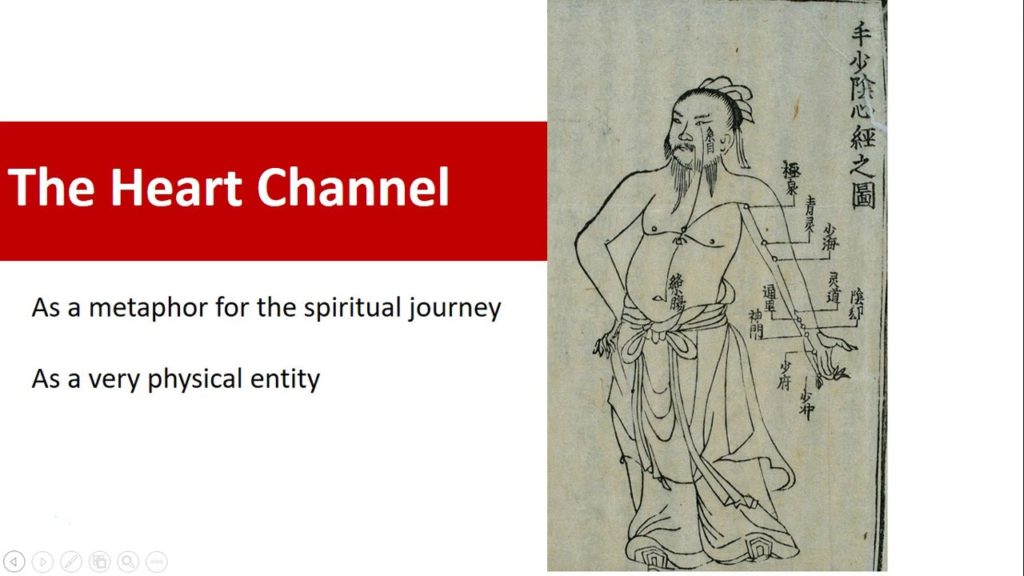

Within acupuncture, the channels most affected by “Gui” and phlegmatic conditions can be the heart and Gallbladder, both of which empower animation, excitement and decisive action. Due to turbid interference, these channels fail to fully activate. We may start feeling as if we are living at 50% capacity in our lives. This is because, due to the “gui” and its distracting influence, much of our energy is blocked from being accessed. This is why “gui” are often described as “hungry ghosts” that steal away our vitality, and even our lives. A drug addiction is a good example of a hungry ghost. The addiction becomes more important than anything else in life. It steals focus, time and energy. But there can be many shadings of “gui” states, some more subtle, others very dramatic and destructive.

Sun Si-Miao, a great Chinese Medical scholar of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 BC), detailed the influence “gui” can have on a person’s life. The person begins acting or feeling a bit “off.” The person feels like he is not quite himself. Soon he may also begin acting not like himself: going to places and doing things that are not in character. The person begins to isolate, protecting his fixations and secret activities. The person may feel controlled by these fixations. Inevitably, his health will suffer, and he will experience inflammatory and even degenerative symptoms. The “gui” has taken over control of the spirit. The spirit may have no choice but to depart. Loss of spirit is loss of life. Miao warns that “gui” can eventually consume and kill us if we let it.

It’s interesting to note that Miao’s description of “gui” sounds much like the modern description of addiction and serious mental illness: the isolation, acting out, secretive behavior and self-destructive tendencies. This can also describe depressive and suicidal states as well. Are they due to a “ghost” having invaded the person, or is the addiction itself the ghost? It could be that the idea of “gui” is a metaphor for mental illness and addiction which can take over a person’s life, robbing them of their vitality and joy.

The image Miao presents resembles the behavior of an addict. The “ghost” image is also reminiscent of a mental fixation, like paranoia, obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression.

A “gui” resonates with the “yin” (more substantive) aspect of the human spirit. Within Chinese medicine, especially that of the tradition of Sun Si Miao popular during the Tang dynastic era, diseases and disorders were classified according to the type of body humor that was out of balance. In diagnosing a patient, it must be determined if the problem is due to fluid malfunction such as phlegm or a problem with the blood or Qi (vital functional energy). Within classification of mental disorders, issues that are characterized as being unconscious, behavioral or mysterious are often due to phlegm. Whereas issues that have more of a conscious nature to them are due to a blood disorder. Both fluids and blood are considered “Yin”humors, whereas Qi is a “Yang” humor. What this means is the Yin humors of the body relate to the more “being” nature of our selves, whereas the “Yang” to the more active “doing” part. Yin relates to how we feel, Yang more to what we do. A “gui” can affect both aspects of a person, but they usually begin by afflicting the “yin.” We start to feel strange before we act strange.

The spirit is always considered to be an important aspect of health within Chinese medicine. In fact, it is also seen as a type of body humor. The spirit is considered to be “Yang” in nature, but like everything there are various Yin/Yang aspects to it. The “Yin” aspect of the spirit is described as the “Po” animal soul, which controls our drives, unconscious, survival, will-focused selves. The “Yang” aspect of the spirit is the “Hun” celestial soul, which is more related to dreaming, planning, visioning and higher mental-emotional-spiritual perception.

The spirit is composed of many aspects. The “Shen” is the spirit-aspect that is most embracive. It is associated with the heart, which is considered the home of the spirit in Chinese medicine: it is the most yang (non-substantive) aspect of the spirit and the most connected to the great spirit. While the “Po,” associated with the Lungs, is the most yin which makes it the most connected to the earth and natural world. The Shen is the most celestial of the spirit aspects, while the Po is the most terrestrial.

The “Shen” is associated with the conscious mind and a sense of animation about life: our sense of purpose. The “Po” relate to primal drives, which operate on the subconscious level. The “Hun” is the intermediary between the “Shen,” which is very lofty in its function, connecting us to our spiritual purpose. It is the Hun that does the fine-tuned work to allow that purpose to unfold.

As moderns interested in using ancient medical practices, we must always synthesize the ancient images, ideas and theories with those from our contemporary culture. Within the field of mental health, spiritual theory has always been considered. Buddhist theorists contribute much to the understanding of the mind and spirit, as do the Taoists within Chinese medicine.

The image of the “gui” is that of losing control of our animal drives. This is why it is considered a spirit disorder. The ability of the Po soul to maintain proper healthy instincts: hunger, safety, sex, becomes out of control. We cannot stop our hunger for these aspects of life. This inhibits the Hun soul from its work serving the Shen. We end up focusing too much of our time and energy on the animal pleasure-seeking aspects of life, and too little on honoring our spiritual purpose: the true work of our lives. We become more animal, and less divine.

As we are getting to know ourselves, in our quest to gain control over our lives, we may notice there seems to be more than one voice inside our heads. Eckhart Tolle speaks of this in his book The Power of Now. Anyone who has meditated for an extended period of time will understand what he’s trying to say.

Part of learning about ourselves is coming to understand which “voices” we are listening to. We can begin to hear the voice of the Po, the Hun and even the Shen when we learn to listen. We can also start to hear the voices of the “gui” as they try to influence our choices. We all have those voices in our heads that say we are not good enough: things we’ve absorbed from others. We also have those voices that continually ask for more food, more sex, more pleasure, often at the expense of our health and sanity.

During my last extended meditation retreat, I observed some rather disturbing voices inside my head. Late into the first day of the retreat, it felt as if I’d entered a hurricane. The storm was inside my head, but no less frightening. My mind was filled with insistent, shouting voices; craving and demanding, manipulating and plotting. The voices were very strong, like bullies that you can’t help listening to and following. The voices were filled with desire to consume and conquer, only seeing the world as a way to quench these desires. The little dictator inside my head was very anxious, threatening me and telling me stories of what would happen to me if I didn’t follow its directions.

What was really disturbing was the realization that I frequently listen to this voice as a guide in life. The experience was a face-to-face meeting with my “gui,” as it was influencing my “Shen” and “Po” spirits. The Buddha called these voices “Mara,” speaking of them as demonic entities that were constantly harassing him. He noticed his habitual tendency to run from “Mara.” The more we resist, ignore, repress and run from Mara the more it influences our behavior. What we resist persists. The Buddha finally discovered he needed to welcome Mara into his life, make friends with him. Only then was he able to reach enlightenment. But like our own friends, we listen to them and accept them, but don’t always follow or believe what they say. We can coexist with our inner demons, but by becoming more mindful, we are less influenced by them.

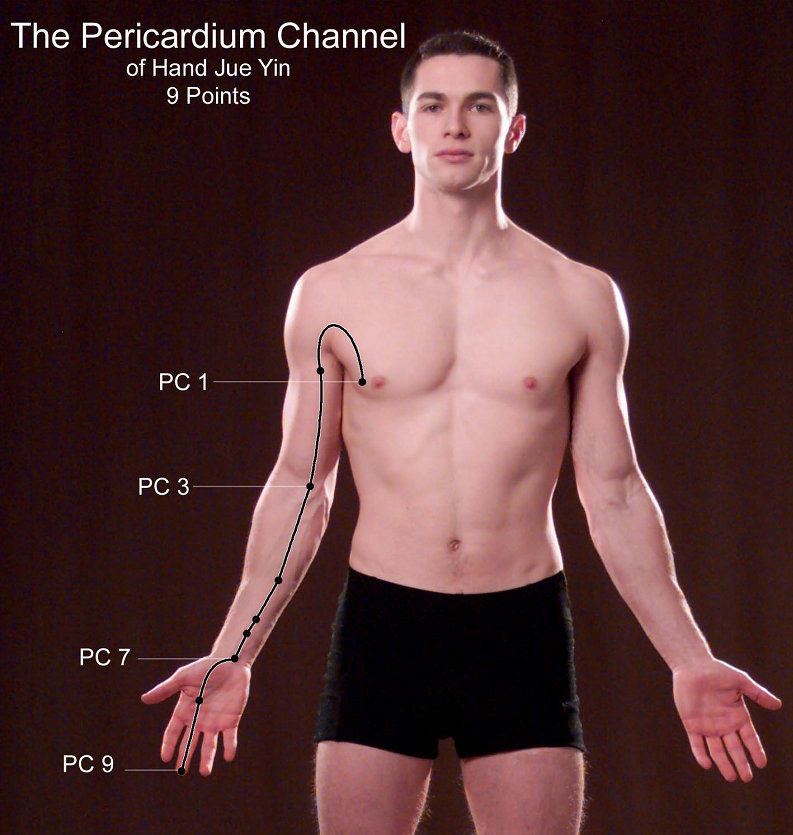

Within acupuncture treatment there are many famous points used for treating “gui.” Many come from the Pericardium Channel.

The strategy for working with “gui” conditions is to transform and/or expel the phlegm turbidity from blocking the portals of perception. This means helping the person work through confusion and delusion by treating the fluid system of the body. When fluids accumulate they can block the sensory orifices: the eyes, ears, nose. However, Chinese medicine also sees the heart as a type of perceptive portal. As the home of the spirit it possesses the most subtle perceptive capacity. When it is blocked by phlegm, this can lead to severe mental illness, derangement and depression. The Pericardium channel is the most effective in clearing the portal of the heart. It is the channel that holds onto disappointments and other traumas.

I frequently converse with my patients about the metaphor of “ghost” during acupuncture treatment. Many people come to my treatment room for support in letting go of obsessions, fixations and addictions. Others feel a sense of confusion, depression or lack of direction in their lives. Acupuncture treatment is a body-mind-spirit healing modality. To work on one level, is to work on all three. Invigorating the “qi” energy of the body can do a lot to break up blood and fluid accumulations disturbing mental and physical function. However, the highest form of healing is empowering patients to learn how to treat themselves. Part of this is learning to listen to ourselves: to become more present. Physically this is working with the Lungs and Heart: the organs of the chest. By promoting stronger Lung and Heart function, the capacity to reflect and be present with what we are thinking, feeling and saying to ourselves becomes easier. This is a respiratory and metabolic treatment, as well as one of mindfulness. When the Lungs and Heart are strong the capacity to “expel” and “vaporize” phlegm becomes easier. Like the Buddha, we learn to observe our inner “gui,” become present them and resist our habitual tendencies to be influenced by their negativity.

Self-awareness is key to health. It is all the more important as we cultivate our capacity to heal ourselves and maintain balance. The healer’s role in this process is as a guide. I’ve devoted my professional life to the study of the human mind, body and spirit. Part of this study is learning to read a person’s energy, through the pulse and through observation of patterns. While it is ultimately up to the patient to make the changes necessary in life, working with a healer can provide insight, direction and support in recognizing and letting go of our “gui.”

No Comments